A Fish Out of Water Part Two: Class and Sustainability

“A Fish Out of Water” is our ongoing series describing the similarities between Fishtown and a community in London called Shoreditch. The series will explain how these communities have adapted over time to the challenges they face. Part One described similarities of both communities through the lenses of their creative environments, illustrious histories, working-class traditions and deep impressions left on those who have lived there.

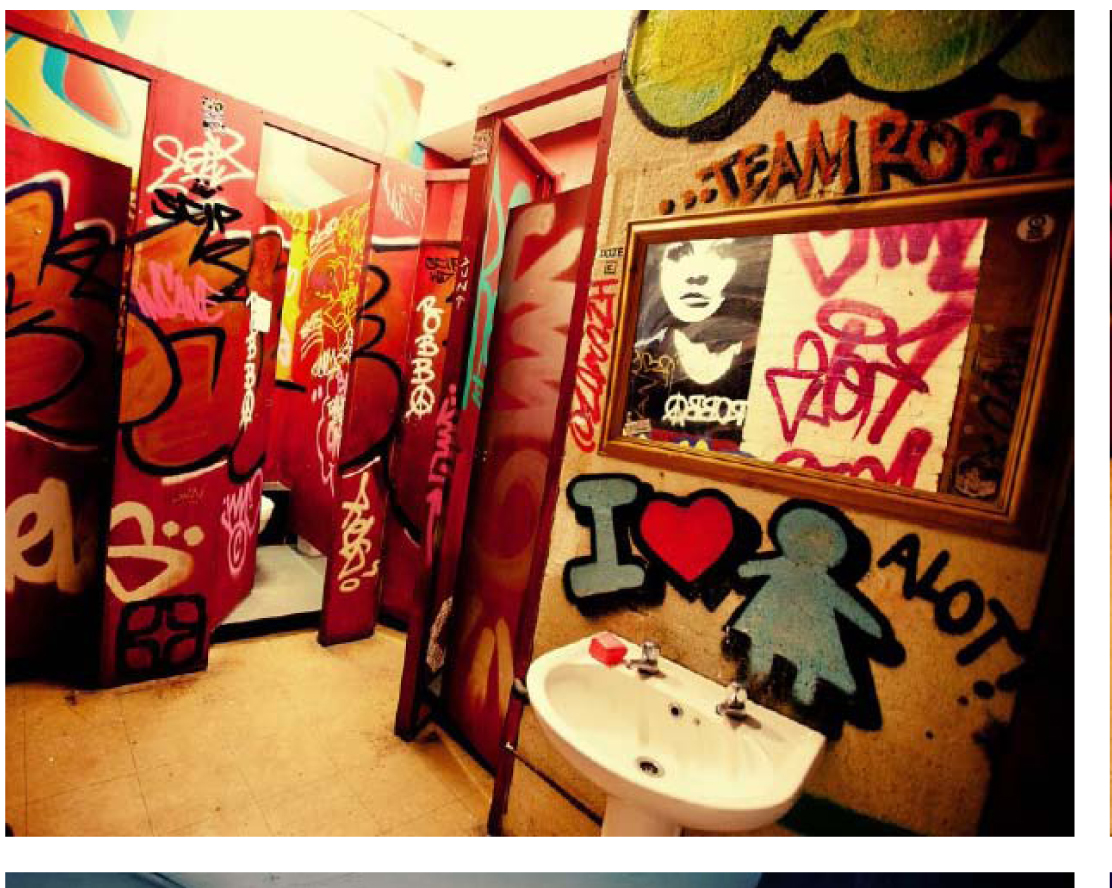

Photos from Shoreditch courtesy Jason McGlad and Kirsty Allison. For full image credits, please refer to the free digital edition of Making Something Out Of Nothing.

These hip and developing communities, heralded as they are, often bear the brunt of divisive generational and class divides. In particular, the alienating divide of cultural stereotypes provoke deep-seated misunderstandings, frustrations, and occasionally points of anger in those who inhabit these neighborhoods.

This section of “Fish Out of Water” focuses on exposing what might cause these tensions in the community and how best to cultivate understanding through a culture and policy perspective. Beneath the tension and misunderstanding there are new, albeit tentative, perspectives circulating. And in it, the power to make these communities sustainable for the long term by harnessing the same creativity and diversity that made them so dynamic.

When speaking on diversity and its role in the community, Nadia James had this to say about Fishtown:

“You can have racially diverse communities but very rarely…is it also diverse in class. What I love about Fishtown, at least in this moment, is that you do still have that class diversity. I think it has a lot to do with the history of Fishtown and that a lot of people have been here for multiple generations,” James, a former Shoreditch and current Fishtown resident, said. “You have a working class and a young professional class and they are all coming together.”

Her claim is backed by statistics. Census data shows a noticeably wider spectrum of median household income, ethnicity, length of housing tenure and education level in Fishtown than in nearby neighborhoods like Mayfair.

Conrad Benner is an artist and photographer who grew up in Fishtown and still lives in the community today. Benner agrees that this blending of cultures and classes has had a unique role in shaping the community but feels as though he has experienced the community through a different lense than James. Benner believes that the cultural makeup of Fishtown is not something that can be garnered from the narrow context of these census tracts or the framework that broader society uses to define class.

“[There’s] this whole idea that working class families are different than the people moving in because [the newcomers] are creative. I would almost argue that the people moving in are in fact the new generation of working class,” Benner said. “This is the economy of the 21st century. I work in digital marketing and these are the jobs that are available to us. Everyone is working class.”

Kirsty Allison, an English writer, professor and filmmaker, echoes similar sentiments from across the pond:

“I wouldn’t use class to determine people. I just think that the class categories have become outmoded and they are no longer relevant.” said Allison. “The creative people that are actually doing innovative work rarely have that much money.”

As we reported in Part One, Shoreditch boasts a large population of creative people working in an array of tech, art and creative industries.

According to statistics from accountants at UHY Hacker Young reported in London’s Financial Times, 15,620 new businesses were set up in and around Shoreditch between 2013 and 2014. In addition, 305,000 sq. ft. of office space was rented to startups, about double the amount in 2012. With this new, booming industry Shoreditch has been dubbed by many as the primary hotspot of digital creative industries in all of the UK.

Regardless of Shoreditch and Fishtown’s ongoing development of industry and the class discussion that surrounds it, both communities have a distinct collaborative nature where everyone seems to help one another.

As James puts it, “People are trying to build one another up.”

As people build each other up in a personal and professional sense, the ways in which each community has been structurally built up differ. The types of buildings and construction projects happening in each area and how those spaces function within the community highlight some of the major differences between Shoreditch and Fishtown.

Fishtown has always been a largely residential area with rowhomes and condos making up a large amount of landscape, still remaining that way even following the continuing influx of people to the community. As more people have moved into the neighborhood, so has development of additional low-rise residential spaces to accommodate the growing population.

Photos from Shoreditch courtesy Jason McGlad and Kirsty Allison. For full image credits, please refer to the free digital edition of Making Something Out Of Nothing.

In Shoreditch it’s a much different tale. Before The Young British artists moved there in the 1990s there was actually not a lot of residential space in Shoreditch. Because of that, the area and its property values are currently booming and developers are flocking in to build more.

“There is a supply issue and there is also a rent issue because of the way that housing is done in London and in the UK. There is not enough social housing in general and the total amount of housing is also going up and as a result you have a crisis from the supply side,” Wong Joon Ian, an East London-based journalist, said. “Add to this a spike in global demand because global investors view London property as a desirable and safe asset”.

It’s not just that people are being displaced and forced out of their houses only because the rent is rising. Ian says it also has to do with the fact that a large amount of new residential space is being built to accommodate the influx of high-income people moving into the area, most of which is high priced real estate.

“You have declining supply and increasing demand from outside. So the people who do get squeezed are the people who don’t have the capital to compete with the demand and don’t have the capital to find new supply,” said Ian. “But you have to ask yourself who is that new supply for, who can afford that new supply?”

Some would say the biggest and most controversial “new supply” of housing and real estate on the horizon in Shoreditch is the Goodsyard, an £800 million ($1,254,240,000) mixed-use scheme by joint developers Ballymore and Hammerson. As reported in the Financial Times of London, if the project obtains planning permission more than 1,450 new homes and 600,000 sq ft of office space are set to be built.

“There’s a lot of money in Shoreditch at the moment,” said Matt Cobb of Hatton Real Estate in the FT. “That can be a good thing and it can be a bad thing, because whatever you decide to build you have to make sure you won’t be destroying what made the area desirable in the first place.”

Ian stresses some alternative ideas about the gentrification of Shoreditch in his article, Gentrification Without Displacement in Shoreditch written for the Center For Urban and Community Research Blog.

“Unlike the narrative of commercial or industrial gentrification, in this case, the displaced property owners welcomed the move out of the area. Again, this upsets the narrative of wealthier incoming gentrifiers displacing existing residents,” said Ian. “In the case of Shoreditch there were no existing residents to displace”.

In Fishtown, Conrad Benner believes the traditional narrative of gentrification in his own community may not fully apply either. Benner critiques the framing of gentrification put forth by outlets that influence public perception and offers his own counter argument.

“The media sort of projects this idea that when gentrification happens it’s this clash between cultures, but that’s just not what I have experienced,” said Benner. “On a human-to-human scale and as someone who grew up in the neighborhood, I am very excited to see the way that [Fishtown is] changing in positive ways. Business are opening up, Girard Avenue is getting redone, the highway (I-95) is getting redone, more and more transportation options are becoming available and all of these things are happening because there is a renewed energy in the neighborhood.”

While Nadia James hasn’t been in the area as long as Benner has, she was in Shoreditch during that neighborhood’s development and feels that Fishtown is starting to reach a similarly uncomfortable level.

“I think that there is actually way too much property being developed in Fishtown right now. Every block I go down I see a new building coming up. The good thing about Fishtown, though, as opposed to Shoreditch, is that at least there are the building limitations,” said James.

Photos from Shoreditch courtesy Jason McGlad and Kirsty Allison. For full image credits, please refer to the free digital edition of Making Something Out Of Nothing.

There are two 42-story skyscrapers planned for development in Shoreditch that have been set on a timeframe to be completed by the late 2020s, as reported by The Independent. This would never be the case in Fishtown though, thanks to specific zoning classifications in the area that would not permit the construction of the skyscrapers currently set to be built in Shoreditch. The only designated zoning code in Fishtown that would permit something close to the 42-story Skyscraper in Shoreditch would be designation SP-ENT.

There are also additional checks and balances on the development of larger buildings in particular areas, including Fishtown. One of these checks that involves the community most is Civic Design Review, a process that occurs when a plan requires both an appeal and a design review. Then there are public meetings and hearings which occur before a Zoning Board, and when City Council considers amending the zoning code they do so with input from the public. Through these processes, the public has some power to influence the development of their own community.

“I think here in Fishtown people want it to be more balanced though so it doesn’t turn into the next Brooklyn, or I mean even just thinking of other Philadelphia communities. There is a reason why people are paying to live here and not Rittenhouse Square,” said James.

In Shoreditch, a number of people in the community sympathize with this same view but within the context of their own community. The Shoreditch Community Association sees the area’s continued development as something that needs to be guarded, regulated and watched closely for foul play.

“There isn’t enough balance on the development. The Council (local government) wants to see only commercial space, the estate agents and developers only want to see residential units—for overseas investors to pay over the odds for but never live in. And the historic locals are trying to protect the historic balance of the area,” said Rachel Munro-Peebles, a leading member of the Shoreditch Community Association. “Everyone, big businesses, companies, and people wants a slice of Shoreditch but it’s only the people who live and work here who understand it and want to protect it.”

Kirsty Allison was part of the movement that lead to Shoreditch becoming cool, and understands the importance of keeping a watchful eye on development. But she also notes that there is an invariable part of community regeneration that we must all come to accept on a fundamental level in order to have progress.

“Change is change, and that’s the thing about it,” said Allison. “That’s the issue with rent control and where artists fit into a community, and whether society values it enough. A lot of people would say that rent control is necessitous to retain a community. There are still a lot of artists and creatives living around here but I don’t know who could get a warehouse now, they would move further out,” said Allison.

With that said the cost of a one bedroom flat in Shoreditch varies anywhere from £335,000 ($513,488.00) to £725,000 ($1,111,280). Additionally the sizes of these flats are regularly priced at £1351.35 ($2071.35) per square foot.

Whatever the multiplicity of factors behind the fundamental changes in communities, it’s imperative that everyone be looking at the issues we all face today through a sense of broader contextual vision.

“Look at how we arrived here. What are the factors driving it? These are global trends and recognizing that, these may not be issues a local council can solve on their own. Maybe there needs to be some redistribution of legislative power or something,” said Wong Joon Ian.

As real-estate prices are skyrocketing in Shoreditch, the market in Philly remains sustainable by comparison. Robert Beamer lives in a repurposed residential warehouse in Fishtown. He sees Philadelphia and Fishtown as a much more economically sustainable environment to live than most other high-priced cities in the U.S., and others internationally. In fact, it was Philly’s affordability that brought him here in the first place.

“Most cities are intensely crowded and expensive,” Beamer said. “But here I can go to a show and see a world-renowned artist, then I can also go to an amazing dinner and not pay an arm and a leg for it and the dinner is going to be really amazing.”

Photos from Shoreditch courtesy Jason McGlad and Kirsty Allison. For full image credits, please refer to the free digital edition of Making Something Out Of Nothing.

James concurs with Beamer and sees our community as an area that may really remain less affected by these global trends noted by Ian in Shoreditch, in relation to affordability and sustainability. She sees Fishtown as somewhat immune to the high, unaffordable nature of city life that some believe is currently affecting Shoreditch. She notes that Fishtown is not next to such a massive financial hub like London, which in her understanding makes it easy to develop since financiers and developers are only a 10 minute train ride away.

“Somewhere like New York or London, they are international cities and Philly is more of a regional city. So I think that plays a massive role in the development of each city because you have all these foreign investors in these other two cities. And yeah they have the money to throw at Brooklyn or Shoreditch and make it what it is becoming. As where in Philadelphia we don’t have the same kind of people, ” said James. “There are very few large enterprises here in Fishtown and for this area thats a good thing. Because when you’re small you can’t bully and say this is what we are doing.”

But regardless of Fishtown’s fundamental and developmental differences to Shoreditch and other large cities globally, by the numbers Fishtown is actually becoming more unaffordable. From the 2003 to 2013 Fishtown saw a staggering 270% increase in home property value.

Local historian Kenneth W. Milano has seen this first hand.

“What does a working person make, $50,000, $40,000? The point is that a working person cannot afford a house in Fishtown, can’t really even afford a house in Kensington,” said Milano. “So you would need 20 percent down to buy a house, 10 percent in a better economy, and then pay $1,000 a month for every $100,000 you borrowed. Well $1,000 a month is a lot of money. So I mean thats still only a $120,000 house, that’s a little row house in Fishtown, not even Fishtown…Kensington.”

Here lies the issue at heart—gentrification and displacement in both Fishtown and Shoreditch.

Some believe these factors could risk pushing members of each community apart from one another if not handled and understood through the proper framework.

James feels, having lived in Shoreditch and now living in Fishtown, that both communities confront the issues of gentrification and displacement on a daily basis and that they have varying degrees of societal impact.

“It comes down to the economics of things. So if the rent is too high then people and business can’t stay here. And it’s the smaller businesses that make it what it is,” said James. “If you have people who are really only interested in themselves and what they do, then those are the same people who don’t mind there being monopolies. But one thing I’ll say about Philly and Fishtown is that everyone is really collaborative and I think that is because the economy has been small”.

With regards to people being displaced in Fishtown, Benner feels it’s an issue that warrants a certain level attention given the climate of gentrification that the community is experiencing. But at the same time he sees his own experience first hand as an anecdote that counters full fledged displacement.

“It’s a question and issue that really needs a study but I can say anecdotally it has not pushed my parents out and it has not pushed me out. And definitely the block I grew up on the vast majority of people I grew up with on that block still live there,” said Benner. “Again, I think that Fishtown has had so much space to grow that there’s room for more people.”

In spite of the fact that Benner feels strongly that there are alternative experiences and viewpoints revolving around society’s limited contextual understanding of what constitutes displacement in Fishtown, he notes though that the increases in the cost of living more generally are, without question, cause for concern.

“An apartment that I would look at three years ago would have been at least $300 to $400 cheaper then it is today. And I do really worry that may really not need to be the case,” said Benner.

Crossing the pond once again back in Shoreditch, Allison believes wholeheartedly that regardless of the community under no circumstances should that kind of systemic and systematic injustice “be the case” as Benner puts it.

“It does not matter who they are no one should be living in a squallored environment if there are people living next door living a good lifestyle. Everyone in an environment should look after each other it does not matter where you are,” said Allison.

“The issue is though whether or not there is a divide being created in the community between the people who have every right to live here and who have their community here and the people who are being sold the lifestyle here for a million pound for a flat. It’s gone to a different level of greed…That is what will destroy it too is mass greed.”