Remembering the Coltrane Legacy in Philadelphia

John William Coltrane, one of the most innovative jazz artists in history, was born September 23, 1926. While most jazz lovers know that Coltrane started his professional career in Philadelphia, many people don’t know the real Coltrane legacy in Philadelphia. There were two organizations that specifically worked to preserve Coltrane’s legacy in Philadelphia – The TraneStop Resource Institute and the John W. Coltrane Cultural Society.

The TraneStop Resource Institute was founded in 1979 by the late Arnold Boyd and named after Coltrane. It’s primary mission was to promote jazz in general and the legacy of Coltrane in particular. Boyd and many others consider jazz to be African-American’s equivalent to classical music. TraneStop advocated for jazz musicans and the genre at-large. Boyd and the TraneStop worked hard to unify and promote Philly’s jazz community. They organized an annual jazz seminar to discuss issues facing the art form and those connected to it. Each year, the TraneStop produced the free Annual Community Jazz Concert featuring local jazz artists and poets, to promote appreciation of jazz as an art form. Later, the TraneStop produced the Coltrane Jazz Festival at Awbury Arboretum. Boyd had also planned an annual, eight-week, jazz-education course for children to help them understand African-American classical music. Since that time, the TraneStop tried to continue Boyd’s legacy under the leadership of Rosalind Plummer-Wood and Ray Wood.

The John W. Coltrane Cultural Society, founded in 1984, grew out of the TraneStop. In 1984, Lovett Hines, asked me to join the TraneStop’s Board of Directors. I was raised on jazz and had attended many jazz concerts as a student at Howard University, so I jumped at the chance to help promote the organization and its activities. Another friend of mine, Eloise Woods-Jones, Philly Joe Jones’ wife, was a board member and explained some of the inner workings of the group. Members of the board included Coltrane’s “Cousin Mary” Alexander, keyboard artist Shirley Scott, jazz singer Dottie Smith, saxophonist/Professor Linda Williams and jazz lover Sophronia “Sophie” Stewart.

At that time, Boyd and the TraneStop primarily focused on promoting the music through concerts and shows. However, Cousin Mary who was a teacher’s assistant for the Philadelphia School District, and the women on the board, wanted to focus on educating African-American youth. We “discussed” that issue with the men on the board for months.

Philadelphia is home to numerous world renowned African-American jazz artists who are virtually unknown in Philadelphia’s Black communities. When attending jazz concerts the audience is comprised of mostly white people, including college students. Where are the young, Black people? We wanted to change that scene.

Boyd began talking about plans for the Coltrane House. “Wait a minute,” Cousin Mary said. “That’s my house and no-one is making plans for my house but me!”

Coltrane and Cousin Mary’s mothers were sisters who lived with their husbands and two children as an extended family in High Point, North Carolina. John and Mary were both only children, and were more like brother and sister than first cousins. After the husbands died, the family moved to Philadelphia and lived for a short time in East Poplar across the street from the Richard Allen Projects. When Coltrane returned from the army, he bought the house at 1511 N. 33rd Street to serve as the family home for himself, Cousin Mary and their mothers. The Coltrane classic “Blue Trane” was composed in this house where he began his spiritual journey.

Cousin Mary asked the women on the board to join her in starting our own organization dedicated to educating the youth. I was a mere 30 years-old — the baby of the bunch. We all agreed, resigned from the TraneStop board and formed the John W. Coltrane Cultural Society. The group was incorporated in 1985 by Cousin Mary Lyerly Alexander, the late Shirley Scott, the late Eloise Wood-Jones, the late Sophronia “Sophie” Stewart, the late Dottie Smith, Professor Linda Williams and me, Marilyn Kai Jewett, — known as “The Seven.” However, it was really eight because Cousin Mary’s husband Billy supported us every step of the way.

The JWCCS was not a “music” organization as such, but more of an educational organization. Our mission was to 1) counteract negative constraints facing inner-city youth through presentations of the positive cultural forces embodied in jazz and other cultural programs; 2) preserve jazz as an American music tradition by making the contributions of African American jazz artists more visible and accessible and 3) preserve the genius and legacy of John W. Coltrane by establishing the John W. Coltrane Cultural Center at 1509 N. 33rd Street (next door to the house).

Our programs included presenting children’s workshops conducted by local professional artists/musicians in Philadelphia public schools, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, day camps and other youth oriented groups. The children were taught life skills using the discipline, techniques and structure applied in learning jazz. Some of those artists included the late drummer Edgar Bateman, African drummer Zaire, and jazz dancer Carla Washington who performed with Sun Ra and his Arkestra. Washington taught teen mothers at William Penn High School how to soothe their babies with music and movement. Although we had left the TraneStop’s board, we still worked with them to promote the music. We wanted to achieve the same things, just using different means. After all, two jazz organizations gave the jazz community a louder voice and more clout.

The city gave us the house at 1509 N. 33rd Street to develop the cultural center. We also obtained a vacant lot down the street from the house and created a community garden that included a jazz mural created by neighborhood youth with the assistance of a professional mosaic artist. The garden was used for summer children’s workshops led by jazz artists and poets like Pheralyn Dove. We adopted Strawberry Mansion High School where a Coltrane mosaic mural was created by the students. Cousin Mary also conducted a lecture series on Coltrane’s life and music at universities and conferences. The Black United Fund of Pennsylvania gave us our first small grant and our first big grant came from State Rep. Frank Oliver who made sure to fund us every year.

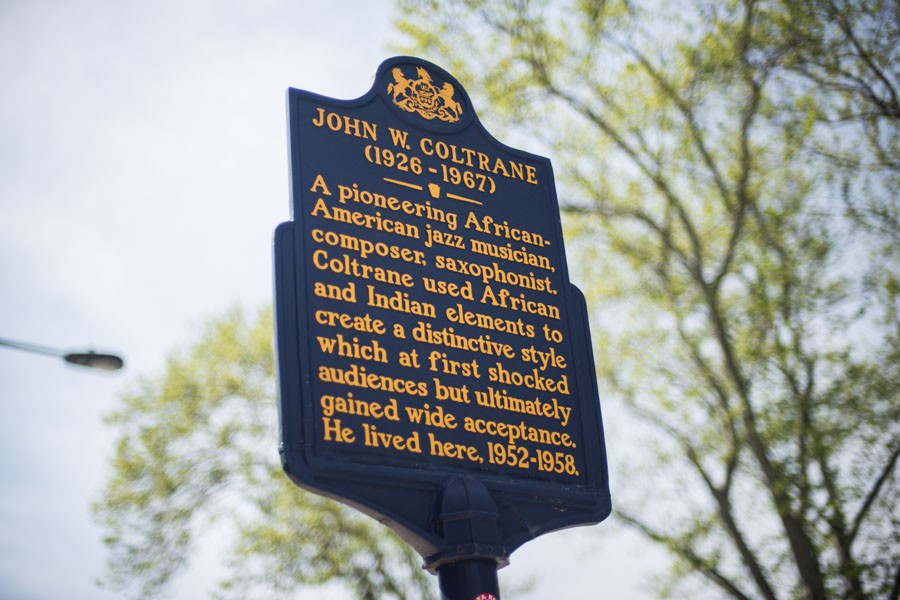

The Coltrane House, where Cousin Mary lived with her husband Billy, was our headquarters. We spent many days and nights around the dining room table planning how to expose the children to the music and our culture. After incorporation, we immediately began working on getting the house designated as an historic site. The Coltrane House was given historic designation by the Philadelphia Historic Commission in 1990 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. We felt this was important because people in the community walked past the house every day and knew nothing of Coltrane or what transpired at that location. This is part of our history that the people needed to know. Additionally, international tourists would come to Philly and asked to see where Coltrane lived. As a matter of fact, a young, German jazz aficionado who visited Philly each year would come to the house to present Cousin Mary with a monetary donation he had collected from his friends in Germany.

Our major fundraiser was an annual Coltrane birthday celebration and tribute held each year around September 23 that featured internationally known artists including Coltrane’s son Ravi, an exceptional artist in his own right. But, the most dynamic event was the Summer Backyard Concert Series held in June and July that featured national and local professional jazz artists, poets and young emerging artists. True to our mission, we always included youth performers from the Clef Club in the show. Artists like Ravi Coltrane and Robert “Bootsie” Barnes, among others headlined at the Backyard Series. The community supported those concerts wholeheartedly and there was always a traffic jam on 33rd Street on those days. People were thrilled to walk through the Coltrane House and sit in the backyard to hear the music up close.

Cousin Mary’s husband Billy is buried in the yard. We planted a tree with his ashes because Billy loved sitting and chillin’ in the yard under the tree. After Billy made transition, Cousin Mary moved and sold the Coltrane House to Norman Gadsen in 2004 before she had the last stroke. Gadsen made transition and left the house to his young daughter.

Sadly, Cousin Mary had a massive stroke which rendered her speechless. She resides in a Center City nursing home. The original organization has been defunct since then.

Shirley, Eloise, Sophie and Miss Dottie all have made transition to the great jazz jam session in heaven. Linda is somewhere teaching music out west in the Dakotas and that leaves me. I will cherish those memories of my time working with the TraneStop and the women of the JWCCS forever. The ancestors have charged me with making sure the work we did on behalf of our youth and this city is never forgotten. Thanks to those who continue to perpetuate Coltrane’s legacy. However, you must not forget that on which the legacy was built. So, when people speak of the Coltrane legacy in Philadelphia, they must never forget to mention, Arnold Boyd, the TraneStop, Cousin Mary, “The Seven”, and the John W. Coltrane Cultural Society and remember — teaching our children our culture is the most important thing. •