The debate over sanctuary city status is a hot topic, both locally and nationally. For years, cities like Philadelphia were forced to pick up the tab when rounding up and detaining undocumented immigrants, sometimes indefinitely.

The agency in charge of immigration violations is Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); however, the Philadelphia Police Department was often forced to deal with immigration issues.

City officials looked to ease this burden on the justice system. Under Mayor Nutter in 2014, Philadelphia became a sanctuary city, and allowed certain undocumented immigrants to live here under the radar, presuming they stay out of trouble. This was implemented as a means to stop police officers from acting as ICE agents in addition to their typical duties, all at a cost to the Philadelphia taxpayer. The action would reduce the amount of people indefinitely incarcerated in Philadelphia County as they waited for federal authorities to deal with them.

According to Philly.com, a recent Pew analysis, which based its research on statistics gathered in 2014, revealed that Philadelphia is home to approximately 50,000 undocumented immigrants. The article also states that the total population of foreign-born people living in Philadelphia was about 200,000, meaning one out of every four people not born in Philadelphia is living undocumented.

There are many instances of people coming to America under various circumstances. Some people were born in the U.S. to undocumented immigrants, and others were brought here at such a young age that they had no control of the situation. This is not one of those stories, and we aren’t denying that in the eyes of the law, Brujo de la Mancha is a criminal.

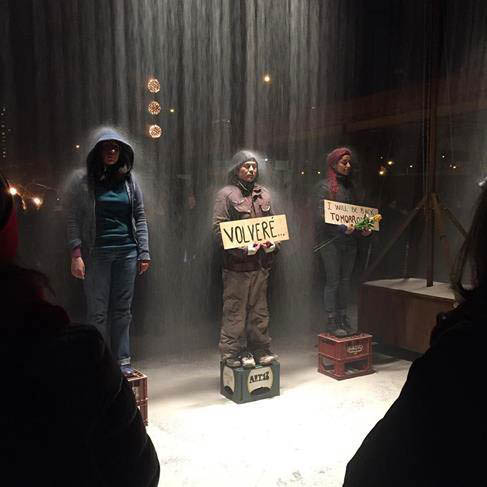

Spirit News was recently given the chance to sit down for dinner with a local artist and teacher who uses the name Brujo de la Mancha, or Brujo to friends. He told Spirit News his real name, but asked us to refer to him as Brujo in this article. Brujo has been living in Philadelphia for nearly two decades as an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. Now he is trying to raise money through Go Fund Me so he can relocate to Canada, and obtain citizenship there.

We casually chatted over homemade lasagna in an apartment in East Kensington, surrounded by friends and children. Brujo has been living in the U.S. since 1998, and spent most of that time living in Philadelphia, working as an artist and teacher of indigenous Mexican heritage.

Most undocumented people aren’t willing to discuss how they journeyed across the southern border and into the United States. It’s often a harrowing, dangerous, and perilous experience. But as we sat at the table, Brujo was gracious enough to share with us how he went from Mexico City to the Riverwards. It wasn’t easy.

Brujo was born in Mexico City in the late 1970s, and considers himself a mestizo, which is a mixed race of Native Mexican, European and/or Arabic.

“I grew up in Mexico City seeing the struggles between native mestizos,” Brujo said.

Mexico has many different languages, dialects and ethnicities comprised of every color in the human race. Brujo told us his darker complexion and Native Mexican appearance led to issues in his neighborhood. “There were some situations in my neighborhood…with my grandmother and my grandfather, who were darker,” Brujo said. “Mexico City has been having this struggle between the natives of Mexico and whoever came 500 years ago, and it’s still happening now.”

Brujo saw the strife and poverty in his neighborhood, and realized education would be his path to a better life. He became politically active and took part in demonstrations advocating for fair education for all Mexicans. On his Go Fund Me page, Brujo writes about one instance where he was being detained by the police after taking part in one such demonstration in 1996:

“I was 17 years old and taken into custody by the undercover federal police that came to the subway after the demonstration. They pulled aside, about 15 of us, drove us around to confuse and scare us, then put us in deprivation for eight hours. They took pictures of me naked and kicked me every time I moved from a squatting position. They threw me out in the streets half naked. I had to cover myself with fabric from the trash outside of the police station. It was one of our demonstration banners. I got home however I could.”

At the time, Brujo was making a humble living as a silk screener. He considers this as the time where he became an artist, though he says he did not consider himself one back then. But his life would change after he met an American girl in Southwest Mexico who was working with the Zapatista Movement, which Brujo was also involved with.

According to mexicosolidarity.com, the Zapatistas were a group that opposed globalization and NAFTA, and supported the rights of indigenous Mexicans, both in cities and in the rural farming areas. On January 1, 1994, the same day NAFTA took effect, the group staged a rebellion in the Chiapas region of Mexico. Clashes between the Zapatistas and the military escalated, which only added to an already volatile living situation for Brujo.

He told Spirit News that gang violence in Mexico City seemed to be leaving someone he knew dead every month. “Sometimes people would say, ‘Run, run, they’re going to start firing,’ so I was used to seeing that violence,” Brujo said.

Brujo says the American girl was compassionate to his situation, and wanted to help him get to the United States. But he had some problems to solve before he could legally pursue citizenship in the United States: He didn’t have a passport, and a legal issue regarding service in the armed forces meant there was no path to the United States without him serving in the Mexican army. “In Mexico, when you’re 18 years old it’s obligatory to do your army service. If you don’t do it, they will not give you an army ID. That means you cannot have a passport,” Brujo said.

According to Brujo, once you were done with required service, the government could force you to stay on and serve in the military, especially with political tensions rising. He saw this as a backdoor conscription of citizens to fight against the growing Zapatista uprising that Brujo was part of. “Sometimes they will tell you that you’ve got to go because they’re not going to waste training,” Brujo said. “To me, I was like, I don’t want to do that. I look at my skin, I look at my face, and I’m like, come on.”

Brujo began to realize there was no definitive path for him to safely get to the United States, but his country’s social issues made one thing very clear to him: He needed to escape Mexico and get to the United States by any means possible. “I started putting it together,” Brujo said. “At that time I was like, ‘I got to go.’ It was too much.”

Brujo says he attempted to cross the border several times on foot. One time he was stuck at the border, and had to find a construction job to make enough money to get home. “I [didn’t] know what to do,” Brujo said.

Brujo later traveled by train to the Tijuana/Mexicali region near California’s southern border with a companion after another failed attempt at crossing. He says the pair toured the border, and as they were leaving a man approached them with an offer. “Out of the blue, this older man came to me and says, ‘Where are you going?’” Brujo said.

The man offer Brujo passage to Los Angeles for $600. After a brief conversation, Brujo and his friend left with the older man to go to a motel. They were told to wait for another person to come in the morning with more instructions.

What ensued, Brujo says, was a terrifying night in the room, with the two Mexicans wondering if they were going to have their organs harvested and sold on the black market. According to Brujo, they slept in shifts to protect each other.

The older man returned the next morning, and explained that they would be traveling in a car, and that they were to tell anyone who asked that they were all family. According to Brujo, the man then produced a kilo of marijuana, and instructed them to “roll up” something. He says they all smoked to calm their nerves before the journey.

Brujo arrived in a small town outside of Mexicali. They entered a building where another 20 people were waiting. “As soon as you walk in, they tell you get two bags of bread, three cans of black beans, two cans of tuna fish and a big plastic construction bag you use to waterproof,” Brujo said.

Brujo described people being packed into a large van, like sardines. According to him, the people were instructed to lay down on the floor, and a carpet was then rolled over top of them. “They put the carpet on us, and the little girl in the front seat,” Brujo said.

Bruji says that the highway the van was traveling on had checkpoints where officers would stop cars and question the occupants. Brujo believes many officers were corrupt, and suspects that they worked with the drivers for a portion of the payout. “It’s like a mafia,” Brujo said.

His entire life was about to come to a head as the van approached a bridge with a drainage pipe running below it. The group was instructed that the van would be stopping and the door would be opening. They were all told that on the other side of the drainage pipe was America.

At that moment, Brujo made that life-changing decision to walk through that storm sewer and start a new life in the United States. “We walked through there, and then supposedly we were in the United States in the middle of nowhere,” Brujo said.

Upon emerging on the other side, Brujo embarked on a three-and-a-half-day journey on foot through the hills and mountains of Southern California. He describes stopping for 12 hours on top of a “mountain” as they feared border officers were in the area. The group was running out of food and water, and Brujo was becoming anxious.

Brujo and a handful of others decided to strike off in a different direction from the group. “It was raining for almost two days straight,” Brujo said.

After about three hours of walking, they arrived in a small town in California, where some residents were willing to help them. They were offered a place to shower and clean themselves up inside a church, but they were told that they could not stay.

Some of Brujo’s companions began to get cold feet, and wanted to return to the coyote, which is the name used to describe a person who leads people across the border illegally. That’s when Brujo, thinking on his feet, decided to catch a cab to Los Angeles, where his girlfriend lived, at 6:45AM the following morning. He made plans to leave during the police’s scheduled shift change, believing that this gave him a window to escape. “I have a 15-minute gap to take a cab, and they will not check me.” Brujo took a $350 cab ride to North Los Angeles, passing through another U.S. immigration checkpoint on a highway in Monterey, CA.

Brujo bounced around California, visiting several cities with his girlfriend over the next couple of weeks. His girlfriend was returning to Philadelphia, where she was from, and told Brujo that she had a ticket for him too. So he traveled by bus from California, and arrived in Philadelphia in March 1998. He found a place to live in West Philly, near 48th and Baltimore. “I crossed all [the] United States, and I came to Philadelphia,” Brujo said.

Upon arriving, Brujo managed to take classes at CCP without providing a social security number. There, he developed a special bond with one of his teachers who would give him five dollars before every class to purchase coffees for both men.

Brujo also took an English class, but decided not to finish. He began teaching himself English at places like the library instead. He went four years without speaking much Spanish, and began to feel like he was living in two worlds. “I was in paradise, but at the same time I was in hell,” Brujo said.

As an undocumented immigrant, Brujo became a man living with a dark secret, and he says it affected his personal life. He found solace through meditation, and began making friends who also shared the same beliefs. However, he quickly realized that he traded his problems in Mexico for a new set of problems in America. His girlfriend who brought him to Philadelphia was no longer in the picture, and every promising relationship always came to a head when his immigration status was brought up.

According to Brujo, this cycle went on for the next 20 years, leading up to present day. Throughout that time, Brujo has established himself as a gifted artist in Philadelphia. His work has been on display at the Please Touch Museum, he was an intern for the Pennsylvania Counsel for the Arts, and he had a solo exhibition at the Rocket Cat Cafe in 2008.

He is an expert in Native Mexican traditions, and teaches classes and workshops on traditional indigenous Mexican dances and ceremonies. He also creates art through many media ranging from pottery to murals. One mural is even displayed at Munoz-Marin Luis Elementary School in North Philadelphia.

Brujo also recalls coming to the Riverwards 20 years ago. “When I came to Philadelphia, [if you tried to come] to Kensington or Fishtown, and [if] you weren’t Puerto Rican or white Irish, you almost get beat down,” Brujo said.

He understands many people see him and other undocumented immigrants as job stealers and drains on the system, but Brujo is a worker with a tax ID number. He’s even had to pass many of the same clearances and background checks many teachers face before being allowed anywhere near children. “FBI knows I’m here because to teach my classes for different nonprofits, I had to get my finger printed. To work in different schools, I had to have my child abuse clearance,” Brujo said. “They know I’m here.”

Brujo mentioned a time when his FBI clearance had expired, and he had the nerve to call the FBI himself to get to the bottom of the problem. “I called the FBI, I said, ‘This is my name, and I’m looking for my results,’” Brujo said. He was unable to use his tax ID number anymore, and when the person asked for a passport or a social security number, he was unable to provide it. This became another problem for Brujo since he often works in schools teaching students.

Brujo says there have been instances where he wanted to leave the United States, but he always stayed because he was doing okay. However, the current political situation has him ready to move out of the United States for good.

Brujo doesn’t see President Trump as his enemy, but after living through three presidents and now another, he doubts Trump will be able to enact real change that will help people like him. “People like me, basically you cannot fix anything,” Brujo said. “That’s when I said, ‘I’m getting out of here.’”

Brujo has looked into paying his way to Ireland for $10,000 through a school, and found that he was qualified. He would have gotten a visa, financial aid and a path to Irish citizenship if he chose. The problem was money, and his artwork wasn’t selling. “Nobody had money to [lend] me,” Brujo said. “Nobody wanted to buy art, I went home and cried.”

He’s also looked into moving to Sweden and Australia, but the path to those countries are either too expensive or require him to return to Mexico before proceeding. Brujo then began looking into immigrating to Canada. He found that he had most of the qualifications, and would be moving there under an entrepreneur cultural visa. “I have to create my own job,” Brujo said. “It’s the same thing I do in the United States.”

However, finances again proved to be the biggest barrier for Brujo to move. He began searching the internet for ways to move to Canada. He found a lawyer with a website offering a questionnaire on whether the applicant was qualified to move to Canada. According to Brujo, the second page was financial information, and had different instructions for people with savings ranging from $10 – $50,000. “Basically if you’ve got $50,000 you can buy a green card,” Brujo said.

Brujo quickly learned that being undocumented made it hard to leave the United States. “It’s more difficult to get out than it was to get in,” Brujo said. He’s realizing that he will need to leave most of his life behind in order to have enough money to move. He remembers coming to Philadelphia with a backpack and $40 two decades ago, and says he’s starting to accept that he may have to leave under similar circumstances.

Brujo says it’s hard to accept the fact that he can only move forward now. Since he doesn’t have a social security number, and hasn’t worked in Mexico in decades, he won’t be able to use services that other taxpayers can utilize, so he needs to become a legal citizen to plan for his future. “I don’t think there’s going to be immigration reform,” Brujo said. “I’ll be honest. I enjoyed the United States. Enough is enough. I know I’m not going to get my social security, so why do I want to be here?”

Brujo has been using Go Fund Me to raise the $11,000 he needs to be able to immigrate to Canada, and as of this past Sunday, he’s just under $700 away from that goal. Brujo’s journey and life as an artist has brought him many great moments, but he believes it’s time for him to move out from the shadows, even if that means uprooting his life.

Brujo is a criminal in the eyes of the law, but he is still a human being, and wants to lose the stigma of being undocumented. “I’d really like to meet Donald Trump to talk to him. Look at me, I’ve never done anything. I’m not a criminal. I teach kids. If you want to kick me, kick me, but you’re making a mistake,” Brujo said. “I’m not a criminal, so why do I have to be on that stereotype?”