The Astonishing Mutation of Philly’s Real Estate Tax Breaks

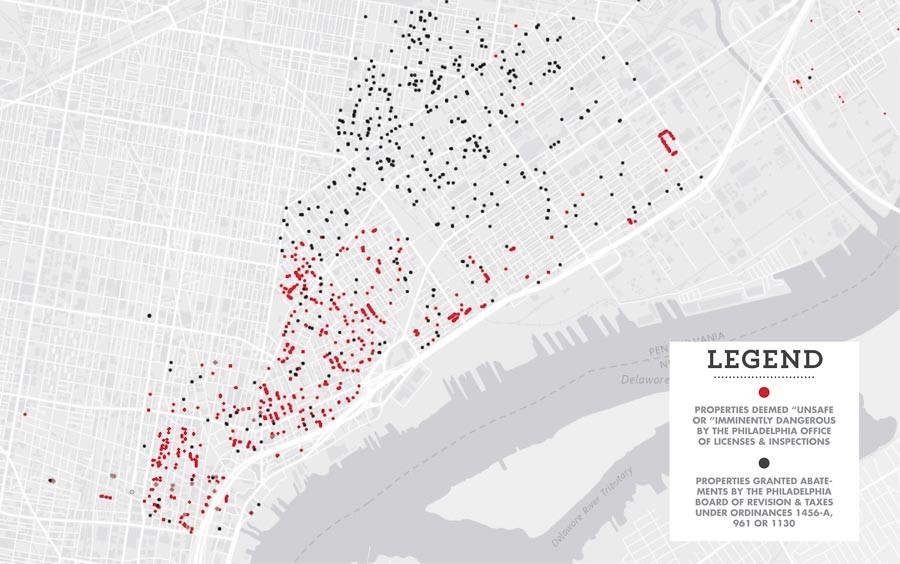

State-owned properties with six-figure liens against them, muggers’ alleys for which no one claims responsibility: the Riverwards are a zoo for real estate anomalies. Not least among these is the strange distribution of real estate tax abated properties.

Residential developers and rehabbers north of Somerset and Aramingo in Port Richmond and Kensington receive almost no tax breaks, though the area has more vacant and ill-maintained property than almost anywhere citywide. Residents of Northern Liberties and Fishtown are meanwhile lousy with abatements.

This begs the question of whether real estate tax abatements actually remedy the problems City Council introduced them to solve. And what were those problems? Added in 1977, Section § 19-1303(2) of the Philadelphia Code states that the

great majority of Philadelphia’s housing was built before 1939, and there are, in all neighborhoods in the City, numbers of occupied and vacant dwellings in need of repair and rehabilitation. It is in the City’s interest to encourage such repair and rehabilitation, in order to preserve and improve the City’s residential neighborhoods.

Philadelphia politicians and other supporters of the plan initially sold the abatements to voters on the premise that they helped out current city residents. Mayor William Green passed a 1983 ordinance granting three-year abatements worth up to $70,000 on building costs for residential projects. The Philadelphia Home Builders Association lauded the idea as a method of “reversing or at least stabilizing the flow of city residents to the suburbs” in an era of steep population declines. The Association asserted this policy would “help the buyers more than the builders.”

Frank Rizzo introduced an additional justification of the policy as one that brings rich people from elsewhere in the country and grows the city’s revenue base. He put this argument in clear terms during a 1983 press conference, at which he promised to attract,

all the people that have got all the money in this country. I’m going to invite them to Philadelphia. I’m going to put packages together that are so attractive that they won’t be able to say no… I’m going to offer them tax abatement[s]. And if they want me to I’ll do the jig up Broad Street.

This has become the argument you hear most often in abatements’ favor today. And the City of Philadelphia has grown ever more generous since Green and Rizzo, granting more real estate tax breaks to more rehabbers and developers for a growing list of reasons. Here is a list of three big ordinances for this purpose in effect now:

Ordinance #1456-A/983 Reason for abatement: Construction of new residential property for sale upon completion

Ordinance #961 Reason for abatement: Improvements to existing residential buildings for sale or occupation by owner.

Ordinance #1130 Reason for abatement: New construction of improvements to existing commercial, residential or industrial properties.

How much do these breaks cost the city? Economist Kevin Gillen estimated we lost about $78 million by way of abatements during 2013. The Philadelphia Office of Property Assessment issued a May report to Council that placed losses at about $37 million during fiscal year 2015.

Whatever the figure, it’s a nose-pincher for some. Properties owned, managed and/or developed by real estate demiurges like Carl Dranoff receive a large portion of the benefits. Dranoff claimed tens of millions of dollars in abatements last year, according to the Philadelphia Coalition Advocating for Public Schools.

Such policies find natural allies in the real estate development industry and lobby. Though, surprisingly, one recent challenge to the program came from within. In 2009, an “insurgent faction of the city’s building industry,” as political scientists dubbed them, courted Council on a proposal that would’ve reserved abatements for green construction plans exclusively. Council didn’t budge.

Public education advocates challenged the abatement again in 2013, proposing a 55 percent reduction in how much rehabbers and developers can write off. This 55 percent would compensate for what abatements cost public schools, as the argument ran. Council didn’t budge then either.

Resilient as they’ve proven in Philadelphia, abatement policies have also gained popularity nationwide. Local governments in 15 states offered property tax abatements in 1964, according to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 37 offered them by 2010.

Executed with proper finesse, local governments ideally recover abatement costs over time plus profit. Kevin Gillen has recently argued that for every revenue dollar abatements cost the city in the short-run, we make two in the long-run.

Abatement boosters also argue they’re a means to entice new residents to move here who otherwise wouldn’t. The city ultimately wins because it can still hit these new residents on sales, wage and business taxes. Assuming they stay, those residents pay more in real estate taxes once the abatements expire. Casinos abide the same logic when they comp high-rollers’ drinks and board.

Another prong of the argument: abatements help cities like Philly remain attractive to developers shopping nationally for potential build sites. It costs more to build in Philadelphia than elsewhere and development investments return less as a result. Abatements to some extent offset these hindrances.

As cities are complicated financial systems, it’s hard to discern whether abatements actually accomplish what supporters claim they do, or it’s just coincidence when the desired effects occur. Supporters of the policy must for this reason often resort to speculative arguments about what would’ve happened if we’d gotten rid of abatements in the past, or what could happen in the future if we get rid of them now.

Say someone ripped all these ordinances off the books in the late 1990s. Two of three new residential units that went up in Philadelphia between 2000 and 2005 would’ve never been built, according to policy firm Econsult. If the abatement ordinances disappeared tomorrow, NYC-based econometrics firm Jones Lang LaSalle wagers we’d lose 3,000 units of residential construction in Philadelphia by 2024.

Let’s assume abatements do pay off over time in all the ways proponents claim they do. Do they actually help current residents other than the real estate industry, which sees most of the funds? Doreen Swetkis in her 2009 dissertation observed impacts in four Ohio cities of abatement regiments similar to Philadelphia’s. She sought to find out whether RPTA [real estate tax abated] properties

had a statistically significant relationship in a desirable direction with the chosen set of indicators of neighborhood change. In other words, the number of homes in a neighborhood would be associated with increased private investment, blight removal, decreased number of crimes, and no change in the distribution of property tax burden.

Swetkis found that while minor crimes sometimes decreased where tax-abated homes concentrated, that was the extent of the benefits. And even those minor perks meant shifting more tax burden to low-income homeowners.

“The results of this study suggest that this policy, as it is currently administered,” she concluded, “is not effective in fulfilling these policy outcomes.”

Despite the lack of immediate social benefits, abatements may indeed help the city stay sexy to rich real estate suitors from out-of-town. But be clear: Philadelphians, more than one in four of whom live below the poverty line, pay for the date whether they like it or not.