Hazmat Laundromat: What’s Up With This Solvent Leak at a Glenwood Ave. Industrial Site

Chlorinated solvents have contaminated soil and groundwater at 2207 West Glenwood Avenue, just south of 22nd & Dauphin Streets. Arbill Industries formerly ran an industrial laundry facility at that site. Perhaps intent on selling the property, the firm now seeks to clean it up, according to a public notice they placed in Spirit of Penn’s Garden last week.

A sign on a building at the Glenwood Avenue address reads, “Paradise Pillow.” An administrative assistant at Arbill said the Glenwood Avenue operation closed in 2005.

Photo Caption: Street view of the building on the 2200 block of West Glenwood Avenue./Laura Evangelisto

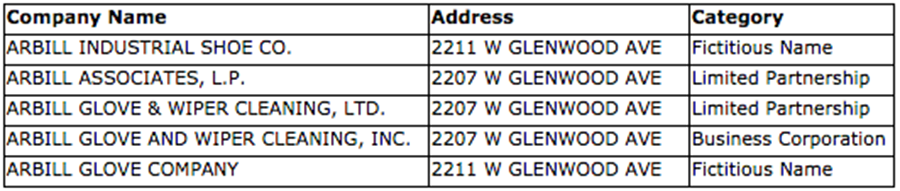

Department of State records label the following businesses “active,” with the following mailing addresses:

Questions regarding the firm’s proposed cleanup plan were directed to Arbill’s national headquarters. The headquarters didn’t respond.

Inspectors with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP) have documented unconfined leaks at the Glenwood Avenue site since at least 2008.

A 2001 operating permit shows that Arbill at their Glenwood Avenue site ran

two 5.5 MMBTU/HR boilers, two heavy-duty petroleum solvent dry cleaning washers, ten textile dryers with built-in condensers, three vacuum stills for petroleum solvent recovery and 26 hampers used to convey textiles in the City of Philadelphia.

They washed toxically dirty laundry: stuff that gets so rank it worries the federal government. Operations like this exist because firms that deal with toxic stuff usually have to ship their workers’ clothes to federally approved incinerators. It’s not cheap and neither is buying new clothes all the time.

Arbill’s laundry company helped firms that deal with a lot of toxic gear clean and recycle some of it for reuse. This saves money on new gear purchases. Arbill also helped ship the unsalvageable gear to federally regulated incinerators.

The Glenwood Avenue facility exported 180 tons of waste in 2005, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

But why would Arbill put an ad in a newspaper about how a defunct facility they used to run is leaking chemicals? The answer to this question requires a brief historical detour.

Federal laws passed in 1980 enabled government to hold anyone that builds, runs or bankrolls projects that result in toxic contamination liable for damages. The laws made it the government’s job to devise and carry out a cleanup plan. Those responsible for the contamination pay the bill.

Finance and industry argued that the laws worked too well. Investors don’t invest if and when they can be held liable for the consequences of their investments.

Money stops moving. Everyone gets sad. Meanwhile, sites like Arbill’s continue leaking stuff into the soil under nearby gardens and public schools because no one will front the money to buy and redevelop such contaminated properties.

In 1995, Pennsylvania lawmakers tried to fix this problem locally by passing Act 2. As one law scholar explains the legislation, it

encourages the remediation and redevelopment of formerly contaminated properties by lowering the environmental cleanup standards, providing protection from liability, and giving financial incentives.

So, Act 2 basically apologizes to investors: “Okay, we promise not to sue you if you get involved with toxic real estate. We’ll also let you decide how clean these sites need to get instead of holding you to the old federal standards. Here’s sweetener money from the public trough. Just, whatever you do, please don’t stop investing in real estate.”

Obviously, these newer state laws diverge from the older federal ones in both practice and intent.

Act 2 also demonstrates a good understanding of state bureaucratic sloth. Companies like Arbill, sitting on less-than-Chernobyl-grade toxic situations, apply and get accepted into the program. Those proposals default into approval after a few months unless state government steps up and actively blocks them.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) requires that owners of chemically contaminated sites publicly display square signs like this one at 2207 W Glenwood Ave. to warn passersby of various dangerous materials nearby and the severity of the danger those materials pose. The number “4” in inside the red box on this sign means materials in this facility may burst into flames if exposed to sparks or heat above 72 degrees. The number “1” in the blue box means the facility contains materials “slightly hazardous” to human health./Laura Evangelisto

PA DEP has blocked three such proposals by Arbill since inspectors first reported the contamination in 2008. The fourth draft of Arbill’s application, however, may have defaulted into approval.

This would explain the notice Arbill placed in The Spirit of Penn’s Garden last week. Act 2 requires that remediators publish a notice with some details about their cleanup plan in a “newspaper of general circulation.” Residents and local government have about a month from when the notice prints to comment on the proposal.

This is mostly a formality. Criticism of these proposals by residents means almost nothing without local government’s support.

Given that Arbill’s on the Philly payroll, it would be awkward for city officials to give such support in this case. And even if city officials did support such criticisms, there’s almost no publicly available information about Arbill’s plan to question.

The notice Arbill published in The Spirit of Penn’s Garden last week simply states the firm wants to perform “pathway elimination.” That’s where you stop up bottlenecks through which contamination travels rather than treating or removing contaminated material. Treatment and removal of toxic chemicals costs considerably more money.

Arbill sued firms Millennium Environmental Services and water testing firm QC Inc. around the time that the Glenwood Avenue plant closed. Those case files might’ve further detailed the contamination. But records from both cases, ID numbers 050100627 and 040502763, have since been destroyed.

PA DEP granted Spirit News an appointment to review state records on Arbill’s Glenwood Avenue site later this month. We’ll publish information from that review in a follow-up of this article.

Photo Caption: Street view of the building on the 2200 block of West Glenwood Avenue./Laura Evangelisto

UPDATE

In an e-mail, PA DEP has explained that the leak resulted from “poor handling practices of the process tanks, lines and washers.” Dangerous chemicals released in unknown amounts at the site include but aren’t limited to Stoddard Solvent, or paint thinner.

A state inspector in 2012 observed groundwater presence of the following chemicals in amounts that exceeded state-enforced limits at the Glenwood Avenue site:

| acetone | ethylbenzene | 1.1-dichloroethane | tetrachloroethylene |

| chloroform | 1.3.5-trimethylbenzene | bis(2-ethylhexyl) | vinyl chloride |

| napthalene | benzene | 4-methyl-2-pentanone | cs-1.2-dichlorethene |

| methylene chloride | 2-butanone | toluene | trichloroethylene |

State officials identified “chronic release[s] from the entire system,” not just the storage tanks.

A company called Compliance Management International handles most of Arbill’s on-site cleanup. Phil Gray, an employee of that firm, responded on Arbill’s behalf to Spirit’s questions about the contamination.

Gray in an e-mail wrote that Arbill,

has been conducting site investigation and remediation activities at 2207 Glenwood Avenue since January 2009 under the direction of the [PA DEP]… Arbill Industries has complied with all requests by the PA DEP for additional data and anticipates closing this case in the near future.

Arbill installed three underground storage tanks at the site in 1982. Together, those three tanks held about 8,000 gallons of hazardous material. The firm in 1999 dug them up and stored them above ground, inside the facility until the laundering operation’s 2006 closure.

PA DEP determined that Arbill employees dug the tanks up without proper certification. The firm “has been out of compliance with Department requirements for a number of years,” according to a 2000 state report.

Another state inspector in 2005 found the “containment structure, for all three aboveground tanks, is not sound due to a number of cracks. The integrity of the containment structure has been compromised for some time now. Problems with the containment area were identified in several inspections.”

The tank system more generally bore visible “structural damage due to flooding and problems with damaged structural supports.”

The “tank supports are broken off,” another inspector wrote. “Dents are present,” they continued,

in the top of the tank from pressure when the tank was lifting [sic.] upwards from recent flooding conditions in the containment area. There is coating failure on the nozzles and shell. Most of the nozzles and piping are bent… The containment also has numerous cracks where moisture or the product can ingress or egress.

PA DEP during a 2004 walk-on inspection observed a “drainpipe with liquid flowing out near [a] dumpster. Liquid was cloudy and dark brown in color… [and] was flowing on asphalt under the dumpster and into a drain.”

Arbill had difficulty with record-keeping and monitoring at this site until its 2006 closure. The firm’s president was at that time “unable to provide manifests for hazardous waste shipments,” according to another state report.

Inconsistent groundwater monitoring presented “a problem for properly characterizing the site,” according to a 2012 PA DEP inspection.

Arbill on their website claims, “We view sustainability as our commitment to the environment, society, the economy, our employees and the communities we serve.”