How to Run a Five-Star Nursing Home

Do The Ratings Reflect Reality?

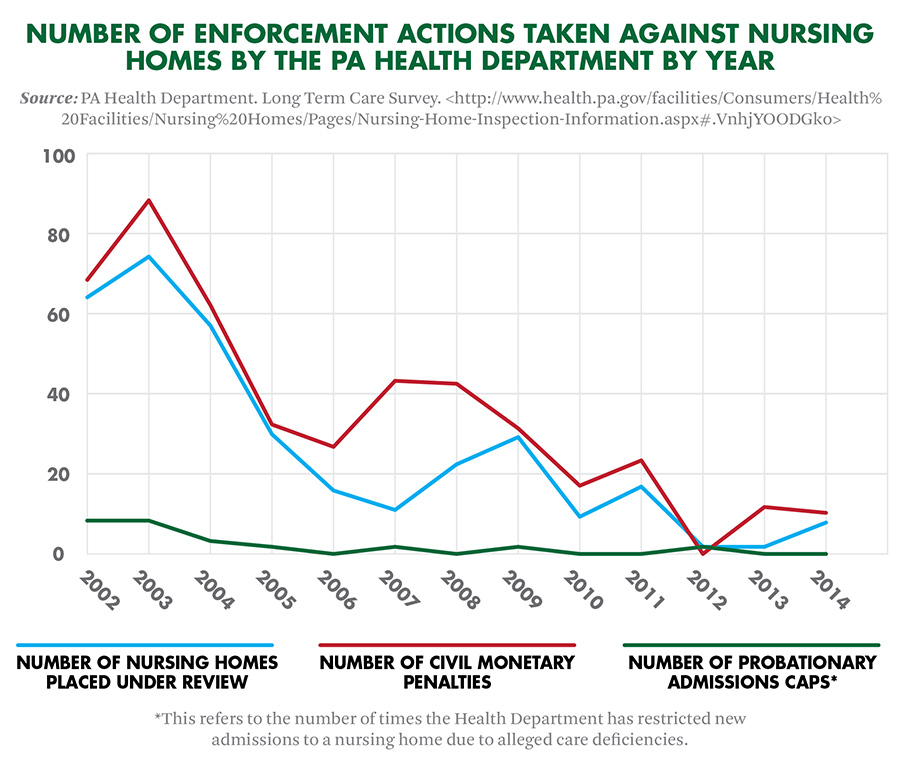

The number of disciplinary actions against nursing homes by the Pennsylvania Health Department has been on the decline since 2002. Either the quality of elder care in the state has improved, the Department has loosened its regulatory controls or something entirely different is going on.

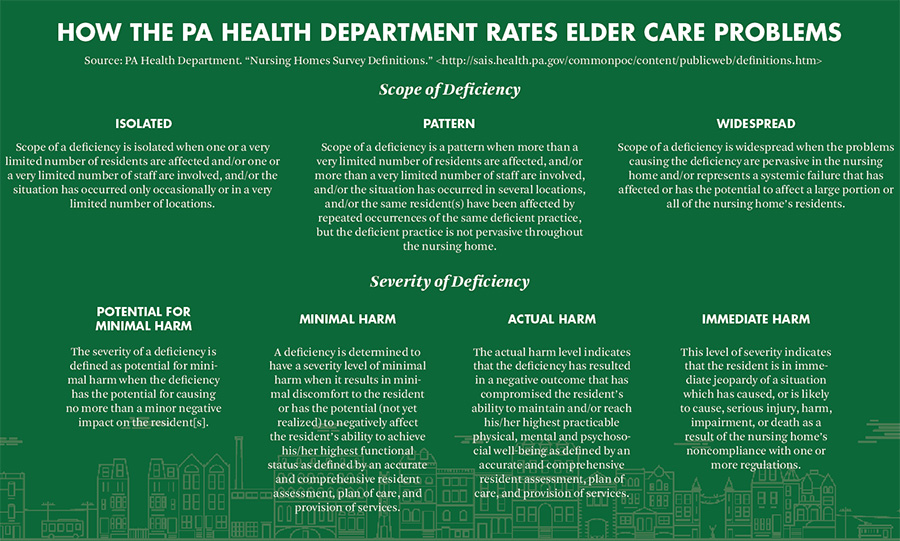

Health Department surveyors inspect all nursing homes that receive public funding. They record each care deficiency and rate it by the degree of harm the resident/s suffered and to what extent these incidents represent chronic problems, based on staff interviews and observations.

These reports ideally remain consistent and sensible, as do the enforcement actions that result from them. Some argue, however, that the Health Department has failed to uphold these ideals. “[I]n Pennsylvania,” the AARP argued in a 2014 amicus brief,

there were many more citations for deficiencies than there were penalties. Nursing facilities know that they will most likely not face penalties for the most serious and persistent violations of the quality care standards, eliminating the coercive incentive to provide care that meets minimum standards.

Between 2012 and 2014, the Department didn’t classify any resident deaths involving staff negligence as “severe harm,” according to Philadelphia law firm Community Legal Services. The Department in some cases recognized resident deaths as “minimal harm.”

What information do these reports contain? Take for example the following write-ups on Philadelphia Nursing Home (PNH) at 21st and Girard Avenue. This isn’t a random sampling. Rather, Spirit picked some of the more serious incidents on record. Another caveat: while nursing homes like PNH would likely dispute many of the claims these reports contain, time and financial constraints may prevent them from doing so.

In 2012, a PNH nurse’s aide found a resident

partly in his wheelchair, at the bottom of a set of stairs… with a laceration upon his forehead… The resident was found to have been unsupervised in the lobby area… [That resident had] exited through the doors, down the stairs, while in his wheelchair, sustaining injuries.

The resident suffered an intracranial hemorrhage after the fall. The Department classified this as an “actual harm” incident, though not representative of a chronic problem.

In 2013, a PNH resident took the elevator to the facility’s ground floor and walked “past the security desk, where [two] security guards were seated and exited the lobby.” Police later apprehended the resident three miles away from PNH’s site. The Department classified this as an “actual harm” incident, not representative of a chronic problem.

A PNH resident didn’t receive medications as prescribed over a two-week observation period this past September due to miscommunications between staff at the nursing home and a dialysis clinic, according to an inspection report. The medications included Aspirin, prescribed as a blood thinner, to reduce heart attack risk. This was recorded as a “minimal harm” incident, not representative of a chronic problem.

According to another Health Department report filed that month, a PNH staffer didn’t wash their hands before or after performing a resident’s tracheotomy. The Department classified this as a “minimal harm” incident, not representative of a chronic problem.

Court records also provide valuable information regarding elder care.

Though the financial interests and biases of involved parties should be kept in mind, “Estate Act liens effectively take the litigation proceeds away from nursing home plaintiffs and put them in the hands of taxpayers,” according to elder care attorney Ron Lebovits. “By and large, my clients have virtually no financial incentive to sue,” he said.

Lebovits is currently litigating a professional negligence case against PNH. The estate of the deceased resident he represents sued the facility and its management company late last year.

Inadequate supervision at PNH led the resident to fall and break both her hips, according to the allegations. She developed pressure sores while bedridden, one of which became infected. That infection among other factors led to that resident’s death.

PNH didn’t respond to a request for comment on the lawsuit, which is ongoing.

According to a similar suit filed by a PNH resident in 2013, that resident required a “left above-knee amputation due to gangrene of his left foot,” and subsequently died of blood sepsis. Purportedly, the resident had no skin wounds when they checked in at the facility five months prior. This case is also ongoing.

In October, the Health Department issued an “abbreviated summary” on PNH. That summary registers “no deficiencies related to the Health portion of the survey process.”

The Center for Medicare Services (CMS), which acts as the federal big brother of nursing home regulators, rates PNH as a five-star facility.

How can what lawsuits and inspections suggest differ this much from regulators’ summaries and ratings? A recent government audit of elder care rating systems suggests some answers to that question. This audit found that while CMS has within the past decade

made numerous modifications to its nursing home oversight activities, it has not monitored the potential effect of these modifications on nursing home quality oversight… CMS cannot ensure that any modifications in oversight do not adversely affect its ability to assess nursing home quality.

For example, CMS has only recently begun to account for how often nursing home staff use physical restraints on residents and how much antipsychotic medication is prescribed to them. The Center has only recently begun to account for staff-hour-to-resident ratios.

The audit of CMS also found that state-level political shifts sometimes influence the prevailing “regulatory philosophy towards nursing homes.”

Consider Long Term Care Provider Bulletin No. 2012-11-13. The Bulletin clarifies which incidents nursing homes must report to the state and which they don’t. Pennsylvania elder care facilities bear no obligation to report injurious falls by residents, erroneous resident discharges, billing mistakes, record-keeping mistakes and medical equipment “misadventures,” though such reports pervade Health Department records.

The “guidance outlined in the Provider Bulletin did not alter or change a facility’s reporting requirements,” Pennsylvania Health Department Press Secretary Wes Culp explained via e-mail. “It merely clarified the reporting process.” Culp also confirmed the policy this Bulletin lays out remains in effect today.