Popping the Hood Off an Economic Stimulus Program in Kensington

Among other factors, some argue that stiff business taxes keep poor neighborhoods poor because they stifle economic growth. If that’s true anywhere, it’s true in a city like Philadelphia, which exacts famously stiff business taxes. To test this assumption, we looked at a Kensington area financial incentive program that funds start-ups. We were interested to see what, if any, financial effect it’s had for area residents.

On the advice of appointed community boards, Philadelphia’s Commerce Department doles out Economic Development Impact Grants yearly to help entrepreneurs start new businesses in certain areas, Kensington included. Local awardees will divvy up around $425,000 in Impact Grant funds this September.

The Impact Grants evolved from a pre-existing federal program first introduced under Clinton: Empowerment Zones (EZs). Local governments receive federal money through the EZ program to help bring business activity back to deindustrialized urban areas. How? By way of start-up grants for local firms, low-interest loans and tax relief on purchases, capital gains, etc.

As the EZ program’s Congressional cheerleaders have explained, the idea is to create an

“economic environment that enables distressed urban and rural communities to have hope for the future through economic and social renewal. Our belief is that when private industry flourishes, it directly impacts peoples’ lives.”

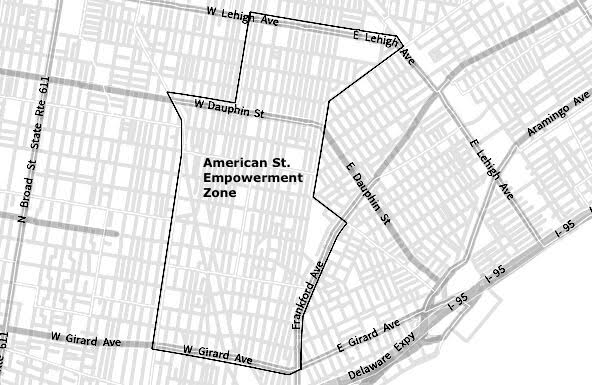

Philadelphia and Camden applied jointly and received $100 million through the EZ program in 1995. Officials split that money between neighborhoods in both cities. Five Census tracts in South Kensington were cordoned off as the American Street Empowerment Zone (ASEZ). The ASEZ received $29 million of that $100 million total.

The benefits ideally trickle down to the neighborhoods. But this would require that officials don’t steal the money first.

In 2002, a high-ranking administrator of Philadelphia EZ funds pleaded guilty to nine charges including conspiracy, theft and mail fraud. Prosecutors claimed former North Philadelphia Financial Partnership executive Jamel Cato exploited an accounting error to double his salary, give himself bonuses and award contracts and low-interest loans to his own benefit.

“[S]everal million dollars of taxpayer money was misappropriated and misused to extents of which it is doubtful that anyone will ever truly know,” according to a LexisNexis case summary.

This was only one among several incidents that involved EZ fund embezzlement in Philadelphia. Atlanta, El Paso and Manhattan have dealt with similar issues.

Though Congress has authorized three generations of grants and tax breaks through the EZ program, Philadelphia has received no additional support since the first.

In 2004, the Philadelphia Commerce Department put what remained of the first federal EZ grant the city received into several trust funds. Of the initial $29 million allocated to the ASEZ, about $4.16 million was invested accordingly. Those funds generate interest. That interest fuels the Impact Grants, scholarships, storefront maintenance projects, etc.

Okay. Aside from the stealing part, how well does the EZ program work? By some metrics, just fine.

The ASEZ makes up roughly half of ZIP code 19122. Census data from 2013 reflects 534 more jobs and 33 more businesses than 2003 data. These increases slightly outpace those in Philadelphia proper during that period.

But new firms don’t seem to be filling new job openings with local people. Unemployment and poverty in the ASEZ has remained all but flat since 2000. Median home value went up almost 400 percent. Median gross rent went up by more than $350 per month.

That’s the economic and social renewal Congress promised.

Surprisingly, the policy by which the Commerce Department assesses Impact Grant program applications contains no “stipulations regarding where employees must live,” according to documents the Commerce Department provided for this article. Applicant firms are “not under obligation to hire from the five Census tracts from the ASEZ.”

Ideally, local governments track firms that receive EZ funds. But many of those records in Philadelphia seem to be missing, hard-to-get or unavailable.

The executive summary of the application Philadelphia and Camden submitted to the EZ program in 1994 is on file at the Philadelphia Free Library. That paperwork would say a lot about how city officials imagined the program would work early on versus how it actually does. But the Commerce Department likely lost the bulk of that 800-page document during the move to its current office, according Vincent Dougherty, Industrial Development Director.

“Everything went to archives at 30th street,” Dougherty wrote later via e-mail.

The Philadelphia City Archives in University City have no Commerce Department documents dated later than 1991 on file.

The forms that applicants submit for EZ funding would also give some insight regarding the program’s performance. But the Commerce Department keeps those documents only seven years after they’re submitted. No digitized versions exist.

Furthermore, the Department said those applications for EZ funds would be released for public review only on pain of Right-to-Know request. Consequently, requesters see nothing the Philadelphia Law Department doesn’t authorize first. And that’s assuming the documents haven’t first been destroyed or lost in a move.