Education: The Issue That Might Just Make of Break the Future of Philadelphia Part I

This two-part report looks at the current state of education in Philadelphia, the causes of those issues, and possible solutions.

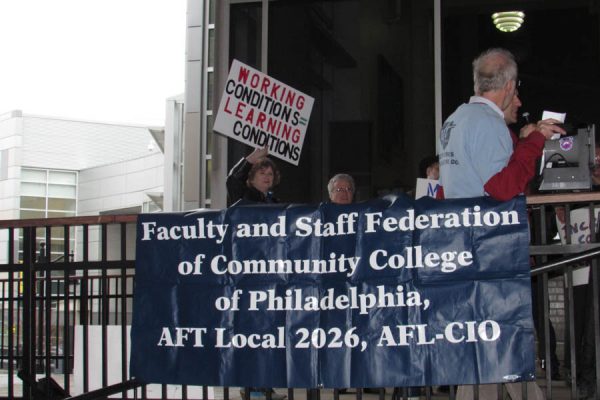

Education in Philadelphia is broken. As budgets fall, classroom sizes rise and heated debates about school system funding continue on, children in the school district become disenfranchised in their own learning process. With the odds stacked against them, parents may not see a long-term future in Philadelphia as problems for the city and its schools continue into the new year.

The latest national assessment of Philadelphia’s school district success rate has shown to be below standards– just 14 percent of Philadelphia fourth-graders were proficient or better at reading, compared to 26 percent in other big cities and 34 percent nationally. Of the 25 largest U.S. cities, Philadelphia ranks 22nd in college degree attainment with only about 10 percent of the School District of Philadelphia’s alumni going on to earn college degrees.

According to Mark Kurperberg, a notable independent economist recently interviewed on PBS about Philadelphia’s education crisis, the way people frame their arguments when talking about the school system is done in a way that overly simplifies the situation, while blaming only those in Philadelphia for the problem.

“What you hear is, it’s Philadelphia’s problem. They spend too much money. They have a strong teachers union. The teachers’ salaries are too high. They need to get their act together,” Kurperburg said. “What we concluded is, on the expenditure side, they’re not out of line at all. In fact, they’re low. It’s the revenue side. We have a state that’s relatively miserly in terms of the amount of money it gives to any of the school districts. It’s the ninth lowest state.”

This sentiment is echoed by Philadelphia City Controller Alan Butkovitz in his recently published financial report.

“One of the problems we have in the Philadelphia School District is the total level of funding for education needs to be greater than it is,” Butkovitz said. “I’m talking about increasing the level of support for schools so that the public schools also have the capacity to provide the amount of services that the charter schools credit with student performance.”

University of Pennsylvania Historian and Sociologist Dr. Tom Sugrue discussed the nature of the funding formula in an NPR article from last year, in which he had many critiques of the current money system that is still in place today.

“The funding formula is, along with persistent racial segregation, a formula for disaster,” Sugrue said. “Concentrate poor, disadvantaged, minority students together in school districts with crumbling infrastructure, with large classes. And then give them less money to do the job.”

Some looking for a solution to the education crisis have advocated for a greater role to be played by charter schools in the district. But Sugrue questions whether or not successful charters are actually scalable and believes replicating the kind of turnaround seen at some charters is simply too expensive and complicated a process to be expanded to all areas of the city.

Meanwhile, Historian Diane Ravitch doesn’t believe it’s money well-spent. Ravitch points to national data that she believes shows charters are proving to be no more innovative or academically successful than traditional public schools.

“What the charter and choice movement has done is sell the line, ‘All you have to do is look out for your own child.’ So escape if you can and leave everyone else behind. Public education is a civic obligation,” said Ravitch.

We’ll examine charter schools in greater detail in next week’s issue of The Spirit.

Escaping from the crisis altogether is just what some young families in Philadelphia may be looking to do, seeing in their view that there may be no light at the end of the tunnel when it comes to fixing the city’s school system.

Jessica Richardson, a parent who lives in the city, posted her thoughts about the current school situation on Facebook. Richardson’s message explains who she instinctually feels are the real people affected by the education crisis in Philadelphia at the end of the day:

“My older kids were fortunate to have been able to attend a great school in their dad’s neighborhood five minutes from my house, but my plan for my youngest daughter is to apply to several of the better charter schools in my area, as the public elementary school in my neighborhood is among the worst in the city,” she said. “Should I feel guilty about this? I’d hate to be part of the problem, but I want my daughter to have the best education available to her when she starts kindergarten next year. Other than voting, showing up at rallies or writing angry emails, what should a parent like me actually DO?”

To help stopgap the education crisis freefall the Philadelphia School District did actually receive more funding back in September. After 11 months of hard-fought legislative battles, lawmakers in Harrisburg finally passed a cigarette tax. They expect the tax to close the necessary funding gaps for the Philadelphia school district and hold off another round of layoffs for the time being.

But since the passage of the cigarette tax, even the legislative circumstances that allowed the additional funding to the schools has come under criticism by some in the press.

According to The Notebook, an independent news outlet specifically focused on issues of education, the new cigarette tax came with some somewhat potentially controversial strings attached. The new tax was passed in part with a provision that has been less publicized requiring the school district to start accepting applications for new charter schools.

Other school districts in cities similar to Philadelphia are taking steps they believe will be constructive in terms of creating solutions to ongoing problems their schools are facing year after year.

The City of New Haven and New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) announced a sweeping K–12 educational reform, New Haven School Change, in 2009. The district had three primary goals for School Change: (1) close the gap between the performance of NHPS students’ and Connecticut students’ averages on state tests, (2) cut the high school dropout rate in half, and (3) ensure that every graduating student has the academic ability and the financial resources to attend and succeed in college.

As part of their solution to the problems stated above, New Haven partnered with the Community Foundation for Greater New Haven, NHPS and Yale University in 2010 to create New Haven Promise. New Haven Promise is a scholarship program that aims to improve the graduation and college admission rates of NHPS graduates as a way to enhance the city’s economic and social development, attract more residents to New Haven, reduce crime and incarceration and improve residents’ quality of life.

While Philadelphia is a much more populated city then New Haven, many of the same demographics, poverty and crime issues similarly affect both cities in ways that some may consider to affect the outcome of how successful a child’s education may be long term.

According to a Study on the Progress of New Haven School Change and New Haven Promise Education Reforms conducted by RAND (an organization that focuses on providing objective analysis and solutions on a wide range of professionally researched topics) in 2013, the schools of New Haven improved significantly.

The findings on New Haven’s school improvement were that the average scores on state tests improved in the first three years of the reform, which was comparable to districts across Connecticut with similar sociodemographic and achievement profiles. Students in the lowest-performing schools yielded the largest gains in test scores, in relation to forecasts RAND conducted based on performing trends.

Dropout rates in the lowest-performing schools improved and were on par with dropout rates in districts across Connecticut with similar sociodemographic and achievement profiles. The percentage of graduating high school students eligible for Promise scholarships increased through time and college enrollment for all students slightly increased on average regardless of whether students were eligible for the Promise program.

There were still ongoing issues that RAND’s research suggested were areas that the New Haven public school system is still in further need of improvement on. Students still lagged behind the rest of the state in state test scores. Promise Scholars noted changes in school climate when they were in high school but did not perceive specific changes in teachers’ instruction, learning environment, or school safety.

Promise Scholars in RAND’s focus groups did not feel fully prepared for college-level coursework, even after the School Change reform efforts had been put in place. Scholars specifically mentioned struggling with study skills, time management, and self-discipline.

In terms of fixing systemic problems in Philadelphia’s schools there have been other specific solutions suggested and outlined by the Pennsylvania School Boards Association Policy Center for Education and Research.

PSBA recommends the state should:

• Provide local school districts with greater authority to hold charter schools accountable based on continuous performance.

• Look at the operations of one well-performing cyber charter and develop a model for cyber charter operations.

• Improve the state report card to show the performance of traditional public schools, “brick and mortar” charter schools and cyber charter schools rather than just a single statewide report.

• Provide the home school district with performance results of students attending charter and cyber charter schools.

But regardless of what the possible solutions may be, Philadelphia’s education crisis still persists. Whether the problem is with funding, miss-managed schools and resources, competition between charter and public schools, or any of the other multitude of factors people claim to be causing the school crisis, the end result is a burden left to bear for students. Their education is failing them and their future.

Some students believe those involved in attempting to fix the crisis remain mystified by the arguments, semantics and statistics of this highly contentious and complex issue. It’s the students, though, who are the ones forced to live in its depressing and, often times, seemingly insurmountable reality when they wake up every morning.

“You go to school to get taught and become the person you want to be, right… and as the years go by you just realize you are taught nothing, and [the people dealing with the school district, and society at large] accept it,” said Benny Ramos, a 17 year-old junior at Kensington CAPA High School. “When the hell did [the school crisis and state of the education system in Philadelphia] ever become, like, normal? This is just how society shows itself now.”

According to Ramos, CAPA has a library full of books but no librarian to help students after that position was done away with last year due to funding cuts.

Other students at Kensington CAPA echoed the same sentiments expressed by Ramos.

Deionni Martinez, an 18 year-old junior at CAPA, wants to let people knows it just makes her life and the lives of other students incredibly difficult.

“We could sit here and say, we should do this, we should do that but nobody is taking us seriously. Or people are seeing it and just thinking I can’t do anything about it because I am going to get in trouble if [students] speak out against the system,” said Martinez.

In spite of the risk of being reprimanded in their view for speaking out against their own education system, many students like Martinez and Ramos are still trying their best to take direct positive action to benefit the future of their education.

Some of the students at Kensington CAPA, as well as students from other schools in the area, are a part of the group “Youth United for Change” that focuses on fighting for public education and youth rights.

While Martinez sees this group as a positive outlet she believes it becomes frustrating often times after putting so much energy into speaking out and being peaceful in the way they conduct themselves, but still nothing is changing in her view.

“You’re not doing anything crazy, you’re not rioting, you’re not cursing anyone out, not blowing up things, and not killing cops. You remain peaceful and you feel like you are starting to get somewhere because you made some big thing about it, but then you feel like you are still getting nowhere,” Martinez said. “You get tired of doing that and its like, oh maybe if we got everybody to walk out of school, and if anyone got arrested it would be okay, rather than going to a peaceful protest.”

Martinez feels like sometimes students are starting to resort to other methods of getting their message across that are not always the most peaceful, or conductive to constructively helping the cause to benefit and change education for the better in Philadelphia.

A similar message of last resort desperation in a quest to find answers for this complicated problem was also conveyed by Ramos.

“My mom pays taxes for the school district and for the cops and for all that. Why are we not getting any benefits from my mom’s money and the money of over a million other people who pay taxes?,” said Ramos. “It makes no sense.”

Next week, we’ll look at the recent influx of charter school activity in our neighborhoods to examine the ways that the leaders of these schools see themselves as one of the potential solutions to the education crisis facing Philadelphia.