University-As-Business: Fiscal Brinksmanship at Temple University

Temple University (TU) has in the past three years sustained a lot of damage to its public image: sexual misconduct allegations against Bill Cosby; the rather unpopular stadium proposal and the nine-month state budget stalemate.

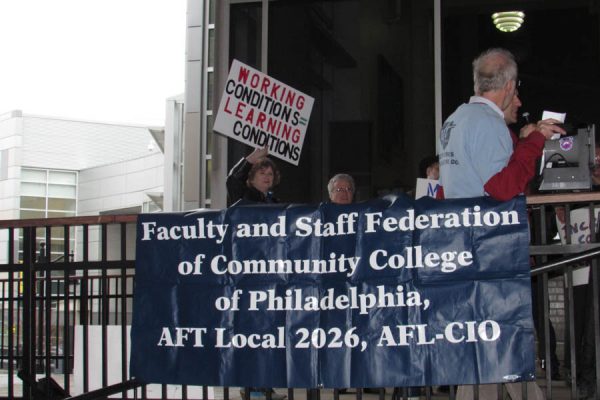

The university has forced out high-profile Black teachers and fought and failed to block an extension of the faculty’s collective bargaining unit to include adjunct instructors. All that’s on top of the standard tuition hikes and faculty cuts.

This fiscal tough-guy, gut-everything policy seems like it hurt the university’s PR operation, too. No one can think up a better way to explain what’s going on beyond the “college-as-business” metaphor: maybe the single most tired line in higher education PR history.

Here’s how it works. It’s not that the state legislature rejected TU’s 2017 funding request because the university no longer acts much like a state school. It’s that TU needs to strengthen its “partnership with the state,” according to TU President Neil Theobald.

It’s not that instruction spending stagnated while the university increased expenditures on everything else. It’s that there’s no “endless pot of money” to pay teachers. That’s what university legal counsel Susan Smith told Temple News last year, explaining the university’s argument against granting adjunct instructors access to the faculty’s collective bargaining unit.

The college-as-business metaphor isn’t wrong. In fact, the administration’s lovers and haters mostly agree: TU does run and think more entrepreneurially nowadays. But just calling something a business doesn’t transform it into a well-run business.

In 2009, Moody’s Investors Service assigned the university a “negative” credit outlook. Despite years of the fiscal tough-guy treatment, this rating hasn’t budged. The university still needs to show a “[s]ubstantial increase in the consolidated balance sheet reserves” to improve its rating, according to a report Moody’s issued in early 2016.

The analysts expressed concern that TU may go $80 million further into debt to build the sports stadium. The university may also have to put tuition revenue toward bailing out their affiliated hospital, which has long operated at a loss. This too gave Moody’s pause.

Business or not, you can’t judge a university by bonds alone. How then does the university-as-business exchange work from a student perspective? Teachers and researchers generate knowledge and expertise, which students buy via tuition, right?

Between 2010 and now, in-state undergraduate tuition at TU increased over 15 percent, controlling for inflation. Room and board expenses increased almost eight percent. TU predicts it will collect $818 million in tuition revenue during 2017.

You’d think this cost increase would mean more and/or better instruction. But TU students actually get less teacher-product now than before. The university eliminated over 100 positions for tenured professors between 2004 and 2014 and increased student enrollment by about 15,000 during that period.

Also since 2004, TU has shoveled a decent amount of teaching duties onto graduate assistants and added more than 200 new adjunct, part-time instructors to its roster.

Why? Business. Full TU professors make about $150,000 a year plus benefits and perks. The university hires adjunct instructors part-time and per-semester. TU pays adjuncts around $5,000 per course minus benefits and perks. The rate varies by department. Adjuncts in the science and business departments usually make the most.

According to one former instructor who wished to remain nameless, TU policy caps adjuncts’ course loads at two courses per semester. “In spring in the English department, it was next to impossible to get a class,” the instructor said. “Unless you were pretty in the inner circle, you could only work in the fall teaching freshman composition courses.”

TU held $470 million in current liabilities (debt) as of June, 2015. How does the school even manage to stay so far in the red despite all these financial whittles? What’d the university do with the $187 million in net surplus it produced since 2009?

If TU actually worked like a public company, you could at least in theory expect answers to these questions at shareholders’ meetings. Police barred Spirit News from the university’s last board meeting due to anti-stadium protests. The next meeting will take place May 10, 3:30 PM on Sullivan Hall’s second floor, just east of Broad and Berks Streets.

The point is this: TU invokes the college-as-business metaphor rather selectively. In fact, few university administrators would be dumb enough to make this comparison for any reason other than to justify their decision to skimp on teacher-product.

Take for example financial disclosure requirements. What would regulators expect of TU if it actually did operate as a publicly traded company and the Internal Revenue Service recognized it as such?

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) requires that such firms list in public filings all current lawsuits involving them, along with potential claims. For TU, this would mean discussing at least 16 open federal lawsuits naming the university and its affiliates as defendants.

The US Department of Education now has at least two Title IX sexual misconduct cases open at TU, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education. Failure by publicly traded firms to report such investigations can also miff the FASB.

Relatedly, federal law would require that public firms rotate auditors every five years. Congress introduced this rule to discourage auditors from developing mutual hand-washing arrangements with clients.

TU would need to make some major changes to meet this standard as well. Accounting firm Deloitte has audited the university since at least 2006. TU faculty speak openly of Deloitte’s involvement in the university’s academic programming.

Don’t expect to hear much about the university-as-business metaphor at tax time either. Claiming charitable nonprofit status, TU saves an annual $4.2 million in tax exemptions on 12 main campus properties alone. This is a fraction of the university’s total real estate holdings, which expand constantly.